The original story is posted on the A&S News Website. Reposted with permission of the author, Cynthia Macdonald, Staff Writer, Faculty of Arts and Science

Bathed in fluorescent light, the sub-basement of McLennan Physical Laboratories has the feel of a secret cave. And like all good secret caves, it’s one that happens to contain treasure.

This is home to the University of Toronto Scientific Instruments Collection: an assemblage of 2000 artifacts that tells the decades-long story of scientific investigation at U of T. Every floor, shelf and corner of its two storage rooms groans with curiosities: mineral samples in old-fashioned baby-food jars; vaccine ampoules; cathode ray tubes; bulky 20th-century machines that appear to have sprung straight from the set of a vintage sci-fi movie.

Although the collection is administered by the Institute for the History & Philosophy of Science & Technology (IHPST), assistant curator Victoria Fisher says that donations to the collection come from every possible scientific department. “Many people don’t know that we exist,” she says, but those who do are grateful. “If you have something very special, you want to make sure it’s retained.”

Along with curator Erich Weidenhammer, Fisher is responsible for the hard work of maintaining and cataloguing the impressive collection. But because it’s what Fisher calls a “shoestring operation”, it’s sometimes hard for the curators to know the exact location of one or another of its riches.

Case in point: a couple of years ago, an email from a Toronto film company made its way to her. They were looking for a special instrument dating back to the 1920s and wondered: might it be lurking somewhere in the sub-basement?

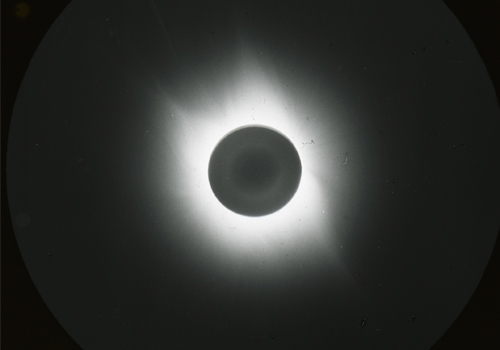

The object in question was a lens known to be part of something called the “Einstein camera.” Designed for use during a total solar eclipse, the camera’s purpose was to record light emanating from stars closest to the sun. It was essential to the success of a groundbreaking expedition that director Alan Goldman wanted to recount in his film.

In 1922, Clarence Chant — head of U of T’s astronomy department and the most important Canadian astronomer of the time — embarked on a two-month journey by steamship to Australia, site of the path of totality of that year’s eclipse.

Capturing the light successfully would provide proof of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity: in those early days after the theory’s announcement in 1915, confirmatory data was still needed.

Einstein’s theory explained the workings of gravity, predicting that a beam of light should bend as it passed by a massive object such as the sun. But in order to test this, the sun’s light would need to blotted out, as during a total eclipse.

Though beset by equipment difficulties, Chant, his team, and his special camera were ultimately successful in recording the bending of light — resulting in an impressive step forward for Canadian astronomy.

But what ever happened to the camera? Responding to the film company’s request, Fisher wasn’t sure it was in her care, but said she’d have a look.

“I knew we didn’t have the camera itself but thought we might have the lens. So I looked through the catalogue for everything classified as a lens — then found this very heavy thing,” she says, motioning to a large, squat object in a wooden crate.

This lens measured six inches in diameter, matching the size recorded by Chant. Knowing its jazz-age birthdate, Fisher examined the newspaper used to pack the lens; sure enough, it dated from the 1920s. She also discovered through an internet search that the use of postage stamps to separate the pairs of glass lenses at each end of the tube from each other was a trademark of the Brashear company, which had made the device and previously used the technique in one that was similar.

“It was very exciting to identify this object, which had been completely unknown and hadn’t been recorded anywhere,” Fisher says. “Yet it’s related to this amazing story, had been to the other side of the world and back, and made this great contribution. It represented a period in Canadian astronomy where people were starting to embark on these ambitious research trips.” The lens actually belongs to an extensive collection of artifacts owned by the David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Once again ready for its close-up, the historic artifact figures prominently in Goldman’s documentary Bending Light. Filmed partially at U of T and co-funded by the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, Bending Light features interviews with Fisher and several U of T astronomers, including Jo Bovy, Roberto Abraham, Adam Hincks and Maya Fishbach.

Being in the presence of the Einstein camera brings one back to a time before jet travel, sophisticated technology and comfortable amenities were available to scientists. It represents but one of the many stories contained in the Scientific Instruments Collection, each artifact of which has contributed to the march of research progress in Canada.

While obtaining her PhD in the history of science from IHPST, Fisher became aware that similar collections at universities across Canada had not received academic attention; her thesis used these collections as a framework within which to explore Canadian physics history. She conducts many outreach activities each year so that people can actually handle the collection’s objects — bringing them that much closer to the worlds of discovery and exploration.

She continually marvels at not only the objects, but the variety of buildings and other sites that testify to U of T’s scientific history. “It’s amazing to have all this stuff on campus,” she says. “I always wish it was better known. Then again, making it known is my mission in life.”

- Bending Light is available for streaming on Super Channel.